It is not a science, it might be engineering, it might be art.

It’s about formalizing intuitions about process. It’s about how to do things and how to develop a way to talk precisely.

So in that sense, Computer Science is an abstraction of Engineering.

This is how the first lecture of the famous MIT SICP starts.

For some time I was flirting with those classes and finally started watching them. In this post (by the way, it’s the first one) I will share some highlights I’ve found interesting in this first class.

Black-box Abstractions

This abstraction is a common ground on all kinds of engineering. You take something and build a box about it.

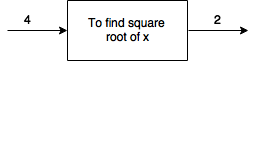

For example the square root method. You can build a box around this method which may contain a complicated set of rules, but you don’t need to know how it works in the inside.

e.g.

The nice thing about this abstraction is that you can compose things without needing to know how these abstractions works. For example the sum of the square root of 4 and the square root of 2.

There are a lot of black-boxes examples in this first class, but I will not spoiler more than the basics :)

Lisp

This is one of the topics covered in this class. Lisp is used throughout all the course. Lisp is a simple language and after learning the basic structure you are good to go to build your own abstractions.

One interesting thing I have never thought about was the way I am used to learn new languages. Usually I start from the basics, learning the syntax and then building new constructions. I’m not sure how others might do this, but the course describes a general framework for learning new languages that I particularly found really nice.

It is described as:

- Primitive elements - These are elements like numbers, strings and etc.

- Means of combination - Take these primitive elements and put things together.

- Means of abstraction - How do we take those complicated things and draw those boxes around it.

Primitive elements in Lisp

3 ; The number 3

12.3

5

+ ; Addition

* ; Multiplication

; And so on...

Means of combination

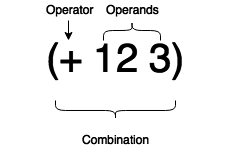

Given these primitive elements, we can build combinations like:

(+ 12 3) ; => 15

Where:

And we can have more complex things, like combining more than one expression.

(+ 12 (* 2 3))

Which means the sum of 12 and the result of the multiplication of 2 and 3.

This expression reduces to the sum of 12 and 6, returning 18 at the end.

Means of abstractions

Take a combination and make it as an abstraction so it can be used as an element in another combination.

e.g.

(DEFINE A (* 5 5))

(* A A)

; => 625

(DEFINE B (+ A (*5 A)))

B

; => 150

Square root example

One of the examples shown on this first class was the square root problem. It is solved in Lisp in this class, but since I was trying to getting back to Clojure again I solved it in Clojure.

The description of the square root method in this class is: (a.k.a Newton’s Method)

- Make a guess G

- Improve the guess by averaging G and X/G

- Keep improving the guess until it is good enough

- Use 1 as an initial guess

Following these instructions, this is the solution I implemented:

(ns sicp.classes.1a)

(defn square

[x]

(* x x))

(defn average

[x y]

(float (/ (+ x y) 2)))

(defn improve

[guess x]

(average guess (/ x guess)))

(defn abs

[x]

(cond

(< x 0) (- x)

(= x 0) 0

:else x))

(defn good-enough?

[guess x]

(< (abs (- (square guess) x)) 0.001))

(defn make-guess

"Try a guess for the square root"

[guess x]

(if

(good-enough? guess x) guess

(make-guess (improve guess x) x)))

(defn sqrt

[x]

(make-guess 1 x))

You can see some of the examples I implemented in Clojure on my github.

Wrapping up

These were some of the things I extracted more value. I highly recommend you to watch it and take notes :)

By the way…

The constraints imposed in building large system are the limitations of our own minds.

There is no much difference between what I can build and what I can imagine.